In October 1944, the United States and Japan engaged in the largest naval battle ever fought. Though it resulted in an American victory and the crippling of the Japanese Navy, realistically, the battle might not have ever happened.

Coming off decisive victories in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea, American commanders disagreed about what their next move should be. Leaders like Chief of Naval Operations Ernest King, Admiral Chester Nimitz, and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall argued that the United States should focus on advancing toward the island of Formosa (Taiwan), which they believed was the perfect strategic location from which to launch an assault on Japan itself.

General Douglas MacArthur, on the other hand, argued passionately to remain focused on the Philippines, arguing that Allied forces should attack the island of Leyte first and then move on to Luzon and Mindanao. He believed that the Philippines would be easier to defend and would allow the Allies to cut off Japanese sea lines of communications. Ultimately, President Franklin Roosevelt sided with MacArthur, and the American plan was put into motion.

On October 20, a few days before the Battle of Leyte, General Douglas MacArthur famously landed on the island of Leyte in the Philippines, addressing the Filipinos and announcing he had fulfilled an earlier promise to liberate the island nation. The Seventh Fleet, reporting to MacArthur, and the Third Fleet, reporting to Nimitz, would be the chief American players in the upcoming battle. The Seventh Fleet, under the command of Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, comprised more than 700 ships, including transports and minesweepers, but was not equipped to fight the high seas battle in its immediate future. The Third Fleet, under the command of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, Jr., comprised most of the U.S. Navy’s firepower, with 17 aircraft carriers, dozens of destroyer escorts, and six battleships. With no supreme commander appointed to oversee the operation, both fleets received their individual orders. Why no overall commander was named remains a controversy today and almost cost the Americans the victory.

The Japanese, for their part, were not surprised by the American decision to concentrate on the Philippines. They planned their own operation to trap the entire American fleet in the Leyte Gulf using a traditional pincer maneuver. Due to significant aircraft and pilot shortages, the Japanese knew they faced a monumental task, so they designed an operation that included employing Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s Northern Force as a decoy in the hopes the Americans would fall for the trap. Ozawa went into the battle fully expecting his force to be destroyed.

On October 23, two U.S. submarines spotted Admiral Takeo Kurita’s Center Force, the main component of Japan’s naval force. Firing upon the Japanese navy, the submarines managed to sink two heavy cruisers, including Kurita’s flagship. More importantly, the Americans now knew the location of the Japanese fleet. On October 24, the battle began in earnest.

The light carrier USS Princeton suffered a bomb hit to begin the conflict, but American ships and aircraft managed to inflict heavy losses on Kurita’s fleet. Kurita ordered his ships to reverse course, a sign the Americans took to mean retreat. Simultaneous to Kurita’s engagement, Vice Admiral Shōji Nishimura commanded his Southern Force, supported by land-based aircraft from Luzon, to engage with America’s Seventh Fleet in the Surigao Strait. By evening, the Seventh Fleet had inflicted heavy losses on Nishimura’s fleet, and Admiral Nishimura himself was dead. By early morning on October 25, the main Japanese force appeared to have been repulsed.

Though victory seemed to be at hand, Ozawa’s decoy force launched into action. Oddly, his force had remained unnoticed by the Americans, despite efforts to gain their attention. With dozens of bombers and fighters finally attracting American attention, Admiral Halsey now faced a dilemma: He could divide his Third Fleet, leaving some ships in position if Kurita returned, or he could commit his entire force to pursuing Ozawa. He chose the latter option, igniting a controversy that rages to this day. Though his orders were ambiguous (remember that there was no overall operational commander), they did, according to U.S. Army official history, include this instruction: “If the opportunity to destroy the major portion of the Japanese fleet should arise or could be created, that destruction was to be [the Third Fleet’s] primary task.”

Choosing to believe his orders required him to pursue Ozawa, Halsey ordered his fleet after the Japanese force. His choice left the Seventh Fleet exposed, with both Admiral Kinkaid and Admiral Nimitz confused as to what Halsey’s intentions were. With Halsey in pursuit of the Japanese decoy, Kurita reversed course and returned to the fight.

On the morning of October 25, Kurita’s fleet reengaged with Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, quickly sinking one of the American escort carriers and several destroyers. The Americans fought back fiercely, against the odds, sinking two Japanese heavy cruisers. Though Japanese victory seemed almost certain, Kurita abruptly called off the attack and retired from battle—another controversial decision perhaps attributable to faulty Japanese communications throughout the battle and the possibility that Kurita was unaware of Ozawa’s success in luring away the American Third Fleet.

Meanwhile, Halsey’s force overtook Ozawa and commenced battle. At this time, the U.S. Admiral received word about the fighting between Kurita’s forces and the Seventh Fleet. Halsey immediately divided his fleet, leaving two-thirds behind to continue the battle with Ozawa and taking the remaining third back toward Leyte. Halsey’s forces sank all four of Ozawa’s carriers, fulfilling the Japanese Admiral’s prophecy that they would be destroyed. Ironically, by losing his carriers, Ozawa managed what no other Japanese admiral had been able to do: He completed his assigned mission.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was a victory that, arguably, American should not have won. Still, regardless of the reason Kurita retreated, the damage was done. The Japanese Navy suffered such intense casualties that they would never again be able to engage in a full-scale action. With Japan no longer a strategic threat, the American forces easily advanced to the island of Luzon and the Philippine capital of Manila, setting themselves up for the ultimate battle for Okinawa.

Of note, the Battle of Leyte Gulf marked the first organized use of kamikazes by the Japanese. These Japanese pilots deliberately crashed their aircraft, loaded with bombs, on enemy targets. This tactic was used from October 1944 until the war’s end as a last-ditch effort by the Japanese after suffering heavy losses at Allied hands. Despite these drastic measures, the Battle of Leyte Gulf proved the critical victory Allied forces needed to invade the Japanese home islands and ultimately win the war.

Battle of Leyte Gulf Casualties

Japanese

- 26 ships sunk, including 3 battleships and 4 carriers

- 300 aircraft

- 12,500 personnel

American

- 6-7 warships lost (with the most severe losses sustained by the small carrier group Taffy 3)

- 3,000 personnel

To learn more about American naval battles during World War II, be sure to visit the Wright Museum! One of our incredible docents would love to help you satisfy your curiosity.

Photograph Citation

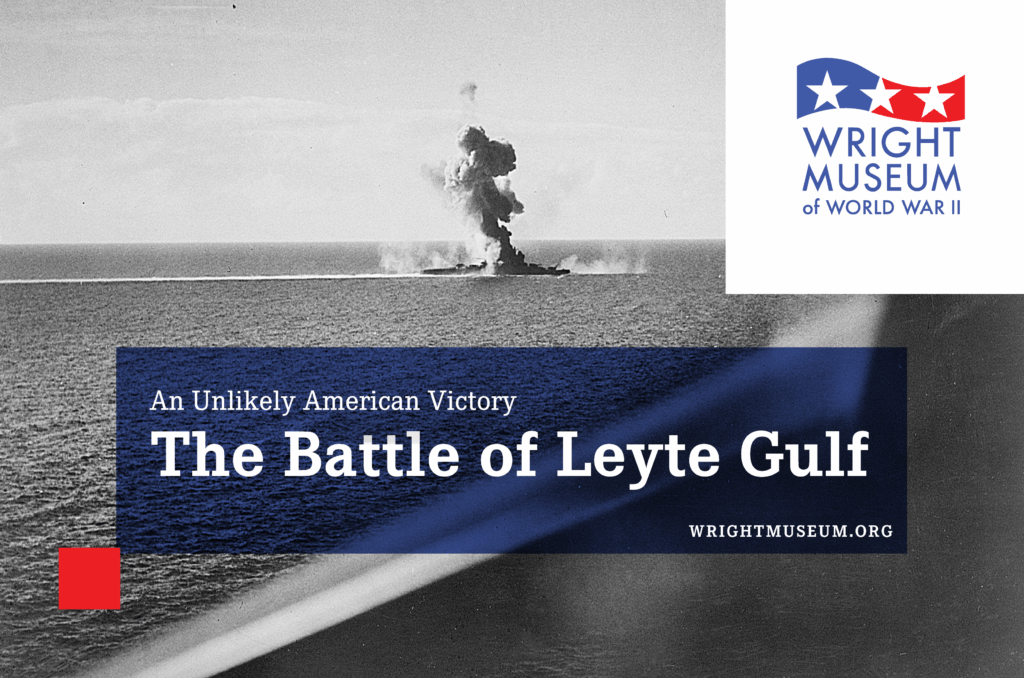

“A Helldiver pulling out of dive after dropping a bomb on the Imperial Japanese Navy ship Kumano.” October 26, 1944. National Archives photo 80-G-47012. General Photographic Files. NAID: 531252. Unrestricted.

For more information on the Battle of Leyte Gulf, please see this article by the National WWII Museum New Orleans, which offers more details and additional resources.