“For those still in the United States, it was very difficult to celebrate. No matter where [people were located] during World War II, they were in survival mode.” – Pam Frese

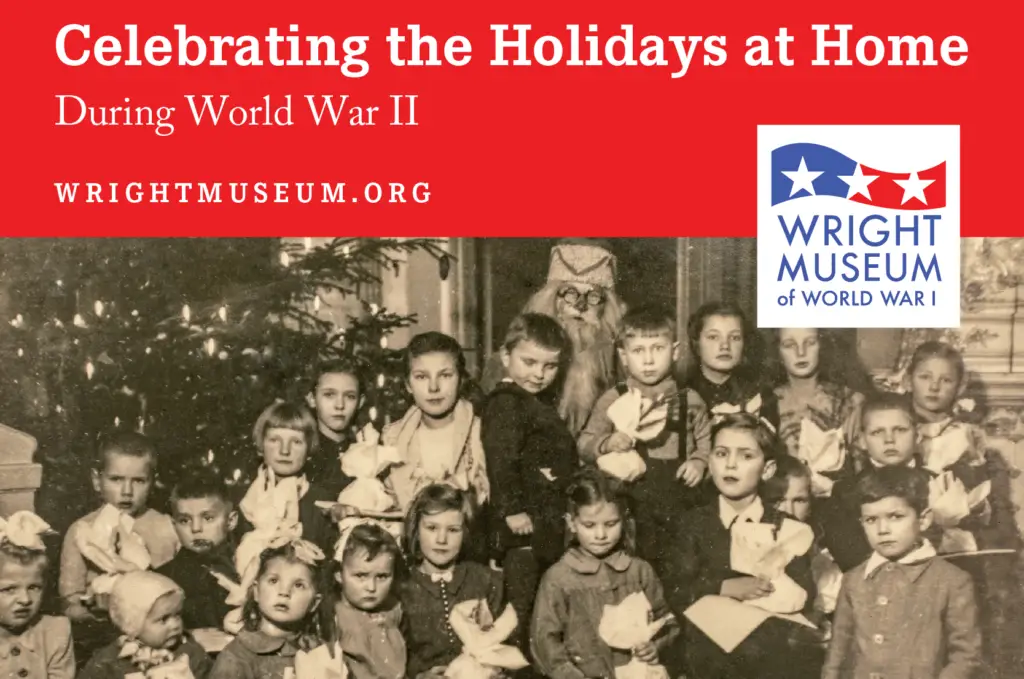

Holidays at home during World War II looked very different from pre-war holidays. Rationing, limited food, and restricted travel added to an already somber tone set by another world war, leading to more subdued celebrations.

Pam Frese, a professor of sociology and anthropology at the College of Wooster and an expert in the celebration of holidays and cultural rituals in the United States, told History.com that women in particular went into survival mode during the war: “While their husbands were gone, women took care of their kids, they worked, they kept things going here. They also, in their minds, took over the role of their husbands and themselves at home.” This reality led to some firsts for the country as it entered wartime holiday celebrations. Women took on the role of Santa for various department stores and community celebrations. In 1943, Blumstein’s department store in Harlem became the first U.S. retailer to hire a Black Santa.

Holiday celebrations changed in other ways as well. Artificial trees rose in popularity. Trees made in America using visca, a type of artificial straw, became popular even as Christmas lights became less so. Blackouts and blackout drills meant outdoor holiday light displays weren’t feasible, while indoor Christmas trees went either unlit or covered as windows were blacked out so light didn’t escape outside. Like those serving overseas, more somber, nostalgic songs like “White Christmas” and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” grew in popularity as those at home dreamed of past holiday celebrations and hoped for a return of peace in the world. Families threw out their German and Japanese decorations, opting for American-made, or homemade, decorations instead.

Holidays became more about sacrifice, with women saving ration cards to gift to neighbors and people purchasing war bonds for loved ones instead of traditional gifts. Homemade gifts gained popularity, with knitting and crocheting becoming popular ways to make presents. Painting and other crafts also gained in popularity with rationing making it difficult to find ready-made gifts. Children’s toys also saw a change during the war. With metal and other materials used to make toys being preserved for war use, toys made of paper, cardboard, and wood took center stage. Popular toys during the war included dolls, wooden jeeps and airplanes, and “Build-A-Sets,” cardboard sets that often had a military theme.

Holiday dinners changed as well. Many families sacrificed turkey dinners so troops overseas could have a taste of home. Instead, families at home opted for smaller birds like chickens or ducks and got creative with side dishes and desserts made around ration supplies. With sugar and butter among the first foods to be rationed during the war, desserts like Victory Cakes and gelatin-based desserts gained popularity, while side dishes would be made from whatever food supplies were on hand.

During the war, around 125,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to prison camps. Those incarcerated used the holidays to retain some semblance of normal life. They would decorate mess halls with found materials, organize caroling events throughout the barracks, and make homemade holiday cards to exchange. Children, convinced Santa couldn’t find them in their isolated prison camps, were delighted to encounter Santa bearing gifts. It was one way of ensuring that the children did not lose their sense of wonder and hope, even in the camps.

Travel during the holidays was limited. Gasoline and tires were rationed items, making it difficult to go any distance. Instead, families celebrated with those in their neighborhoods and sent holiday greetings and messages to each other through letters and packages, just as they did for their loved ones serving overseas.

During World War II, holidays meant sacrifices on the home front, but didn’t mean celebrations were abandoned altogether. Families still attended services at local synagogues and churches. They still gathered with local family and friends. They still had special dinners, and children still celebrated with laughter and new toys. But holidays during the war also meant remembering why loved ones were absent, enduring separations due to war that all too often became permanent, and learning to adapt to a world changed once again by unrest. Americans endured, and in December 1945, the nation was able to celebrate a return to a more festive holiday season—while looking forward to rebuilding a society and nation changed by a second world war.

To learn more about the home front during World War II, visit us at the Wright Museum. Our season runs annually from May 1 to October 31.

All information in the above article was taken from the following sources. For more information on how American servicemen and women celebrated the holidays during the war, please check out the sites below.

Historiamag.com, “‘Put Those Christmas Lights Out!’ The Home Front During World War Two”

History.com, “How Americans Celebrated the Holidays During World War II”

The National WWII Museum, “Christmas on the WWII Home Front”

Sarah Sundin, “Christmas in World War II – The US Home Front”