Setting aside a day to honor those who have died defending their countries is not a new concept. In fact, historians date western traditions of honoring fallen soldiers with large-scale public commemorations back to ancient Greece. Around 431 BC, Greek politician and general Pericles offered a funeral oration for soldiers who died during the Peloponnesian Wars. Ancient Romans performed similar ceremonies and brought the practice to Western Europe during the height of the Roman Empire.

In the United States, Memorial Day as we know it dates to the latter years of the Civil War. During springtime “decoration days,” soldiers’ graves were adorned with flowers to honor the ultimate sacrifices they made. Local communities would determine when decoration days would occur, though efforts to commemorate fallen soldiers were rarely organized on a larger scale.

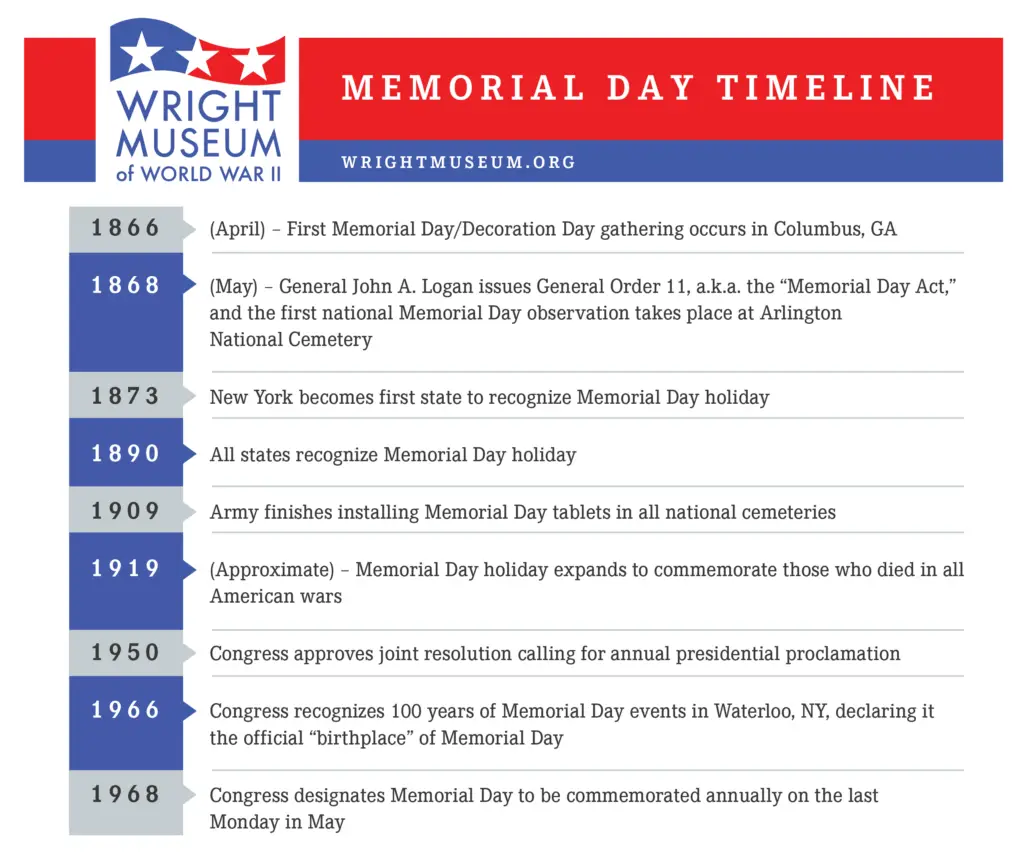

Though there is no documentation to support it being a custom observed more in the post-Civil War south, the idea of a nationally observed Decoration Day didn’t take root until it was spearheaded by General John A. Logan, the commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a politically powerful organization comprised of Union veterans. In 1868, General Logan issued General Order 11 calling for a formalized Decoration Day after prompting from his wife, Mary, who witnessed a Decoration Day observance at a Confederate cemetery in Virginia. The GAR order declared the official national observance day to be May 30, “to ensure availability of the choicest flowers of springtime,” though it allowed for freedom in how ceremonies were planned and carried out.

The first national Memorial Day observance occurred on May 30, 1868 at Arlington National Cemetery, just weeks after General Order 11 was published. The ceremony, held near the Arlington mansion (once home to Confederate General Robert E. Lee), commemorated the burial of around 11,5000 Union soldiers and approximately 350 Confederate soldiers. Of those buried, more than half were buried as unknowns. An existing program from the event shows that prayers, hymns, and a recitation of the Gettysburg Address were part of a ceremony that also saw remarks from future president James A. Garfield. Prominent Washington officials were present, and federal employees were given “free leave” to attend if they chose.

In 1873, New York became the first state to recognize the Memorial Day holiday formally, with all states recognizing the holiday by 1890. After World War I, Memorial Day was officially expanded to include honoring those who died in all American wars. The Woman’s Relief Corps (WRC) took it upon themselves to issue cast iron tablets commemorating General Logan’s first Memorial Day message and donated them to states for placement in prominent locations. The United States Army completed the task by ensuring all national cemeteries had tablets by 1909 as a centennial project honoring President Abraham Lincoln. All tablets replicate the dimensions and appearance of iron tablets cast with the Gettysburg Address.

Congress approved a joint resolution in 1950 requesting the president issue an annual proclamation calling all United States citizens to observe Memorial Day and in 1966 set the date of observance as the last Monday in May as part of the Monday Holiday Act.

Today, we continue to honor those who sacrifice their lives to ensure our freedoms with both large, formal ceremonies and smaller observations in our local communities. We gather with our families and friends, giving thanks for the freedom to celebrate life and togetherness because of the sacrifices of those who fought and died for us. So, this Memorial Day, be sure to take a moment from your fun to spare a thought for all those who have given everything. We know we at the Wright Museum will be doing so.

For more information on the history of Memorial Day, visit the Department of Veterans Affairs Memorial Day web page.